While we were at the chili cook-off a couple of weeks ago, one of the chefs was advertising his business as well as his chili. He owns a boat club franchise, an unknown concept to David and me.

When we first moved to Marble Falls we assumed we’d buy a boat. There are four big lakes half an hour’s drive from our house. But then we learned that we are not allowed to store a boat on our property; it’s against HOA rules, which is understandable because only hillbillies have trailers and recreational equipment scattered around their yards.

So that would mean not only the price of the boat, but the price of its storage; then the hassle of driving a distance to hook it up and haul it out, and the added required time of bringing it home to be cleaned and stocked for an outing. And, as we had a family boat when I was a child, I’m aware that half the time the boat’s out of commission for one reason or another. A lot of things go wrong with a boat. Having fun on the water every once in a while simply wasn’t enough to overcome the bother and cost.

But we do like to bump around on the waves. We’ve rented a time or two, which costs four hundred for a half-day. And we’re curious how this boat club works. So David makes an appointment with the chili/boat club guy and we set off to a marina on Lake Travis.

“I hope this guy doesn’t do the hard sell,” I say. Once, in Bali, an obsequious Indonesian approached David and me on the street and told us that he got paid thirty dollars for every potential customer he was able to bring in for a timeshare presentation, adding that he was trying to support a family and he badly needed the money. My compassion, which is usually comfortably dormant, kicked in; and we accepted the bribe of a free stay in one of their resorts in return for ninety minutes of our time, which ended up being an agonizing three hours of being intensely badgered by a salesman who told us that if he couldn’t convince us to buy a timeshare he was going to get fired; and if that happened his wife was going to leave him. When finally we were allowed our freedom we were drained and angry.

“He seemed okay,” David tells me. “He made good chili.”

We’re to meet him at a private yacht club, which turns out to be a grand edifice on a cliff overlooking Lake Travis. Valet service is complimentary. It’s a clear day, hot for March, and the view over the water is spectacular. In order to get to the marina below, we must descend in a metal box, which squeaks, rattles, and looks rickety.

“Those are awfully small cables,” David says. I assess the cables. He’s right. They’re much too puny to be trusted with our combined weight. We watch as a few people get on down below and are slowly carried upward.

“This is making me anxious,” I say. The car arrives, the passengers disembark, and I bravely step on, closing my eyes so I won’t have to watch as we die.

Bill meets us as we step from the lift. He’s forty-ish, light brown hair, blue eyes. I can tell by his relaxed posture that he’s not going to try to guilt us into buying what he’s selling. A boat transfers the three of us to one of the docks. It’s a large marina—eight extended docks, each accommodating at least forty boats. The surface beneath our feet is unsteady as Bill leads us through the bobbing maze, pointing out the boats that belong to his fleet. He stops at one of the pontoon boats and invites us aboard. No office then, just a man on a boat with an iPad.

He explains the three packages:

Most expensive—one-time joiner fee of four thousand, four hundred a month, unlimited use locally and at the other hundred and twenty locations nationwide.

Mid-range—three thousand to join, three hundred a month, access to other locations, unlimited number of times a month, but weekdays only.

Least expensive—he calls this one “Toe in the Water.” Two thousand down, two hundred a month, not accepted at other locations, use limited to twice a month, and one of those times can be a weekend.

We ask questions—what are we responsible for? Gas. How about insurance? He carries the insurance. Availability? Always, but book two weeks ahead during holidays. How long is the contract? Renewable in a year. The appeal is that we show up, we know the boat works, we get on it, and we go. No maintenance, no storage fee, no trouble at all.

We tell him we’ll think about it and he doesn’t apply any manipulative sales techniques like trying to hold us here, or throwing out better deals, or telling us that his wife’s going to leave him if we don’t buy into his club. He accompanies us back to the central dock and says good-bye. On our way to the lift, David and I take a detour through the little floating shop. I glance at the flip-flops on display in the main aisle.

“Those flip-flops cost a hundred and ten dollars,” I tell David.

“Nobody wants to go on the water in the winter months. So that’s four or five months a year we’d be paying for it when we wouldn’t be using it.”

“An ordinary pair of flip-flops, nothing special about them.”

“But surely we could find two days a month.”

“And look. These beach towels are seventy-five dollars a piece.” They’re nice towels, but not seventy-five dollars worth of nice.

“When you need a towel, you need a towel.”

“We could take a boat out in the winter. We could bundle up and we'd be the only ones on the lake.”

“This is so much cheaper than buying or renting. And so much more convenient.”

We end up going with Toe in the Water. Anyone want to tool around on Lake Travis with us?

The marina from the yacht club.

A tiny car carries people down from the yacht club and up from the marina. The lower building houses a small and ridiculously expensive shop.

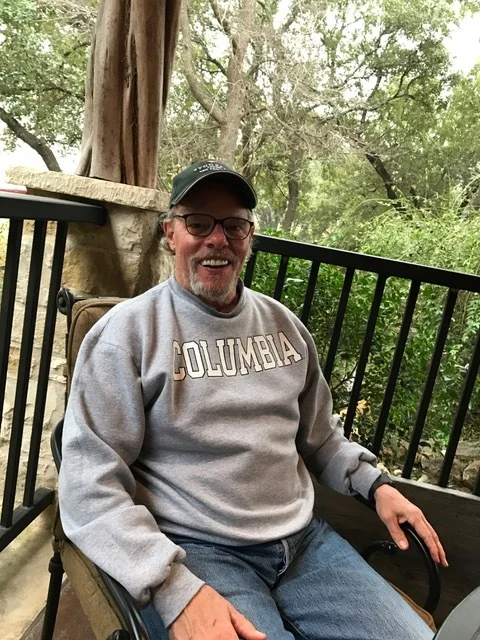

This is me, terrified with eyes closed as we descend. The sweater makes me look fatter than I am--won't be wearing that again!

Boats, boats, boats!