We have reasons to celebrate.

For one thing, Sam and his girlfriend, Julia, visited from Beijing. I haven’t seen Sam in over a year, but other than a different hairstyle, he’s still the wise and inspiring presence he’s always been. I say inspiring because he makes people want to live up to their best. It’s a gift. He’s been busy getting his company up and running, and a couple of weeks ago Mantra had its official kick-off which triggered a huge number of orders and all sorts of favorable responses, including marriage proposals, requests for television appearances, and rumblings about an upcoming documentary. The buy-one-give-one concept is new in China, and wealthier people in the city are enamored with the idea of providing eye exams and glasses to poor rural kids—especially as they’re purchasing a pair of really cool sunglasses for themselves. Yay, Sam! It was good to see both of them and I feel that Julia—British, works for GB’s embassy in Beijing—got a good idea of what Texas is all about.

The next thing to be celebrated is that Curtis and Anna are now engaged. This makes me happy, as the two of them are good for each other. They share the same sense of humor and are mutually supportive. I understand, from speaking with other mothers at this stage, that an upcoming wedding can be fraught with conflicts and petty concerns, but regarding these two, I feel a sense of peace. We love Anna and are happy that she’s to be part of our family. Yay, Curtis and Anna!

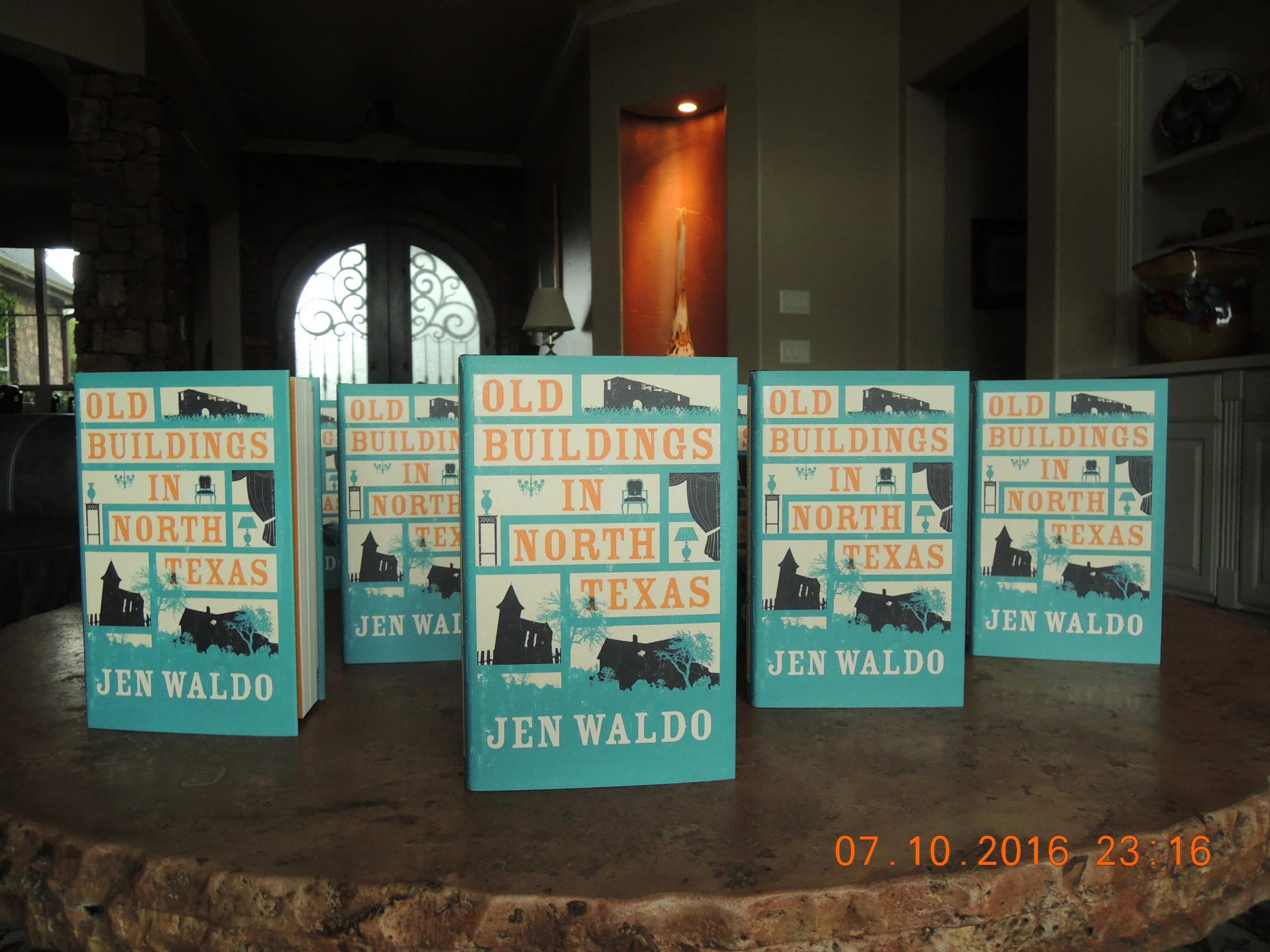

And then, of course, there’s my personal triumph. Old Buildings in North Texas is now on the shelves in Great Britain. It’s obtainable in hardback from Amazon here in the states, and, though both the hardback and electronic versions are available on Amazon.co.uk, UK Amazon isn’t available in the US, so no kindle downloads here. Oddly, the hardback is much cheaper here in the states, so it’s really no more expensive to order the hardback than it would be to get it electronically.

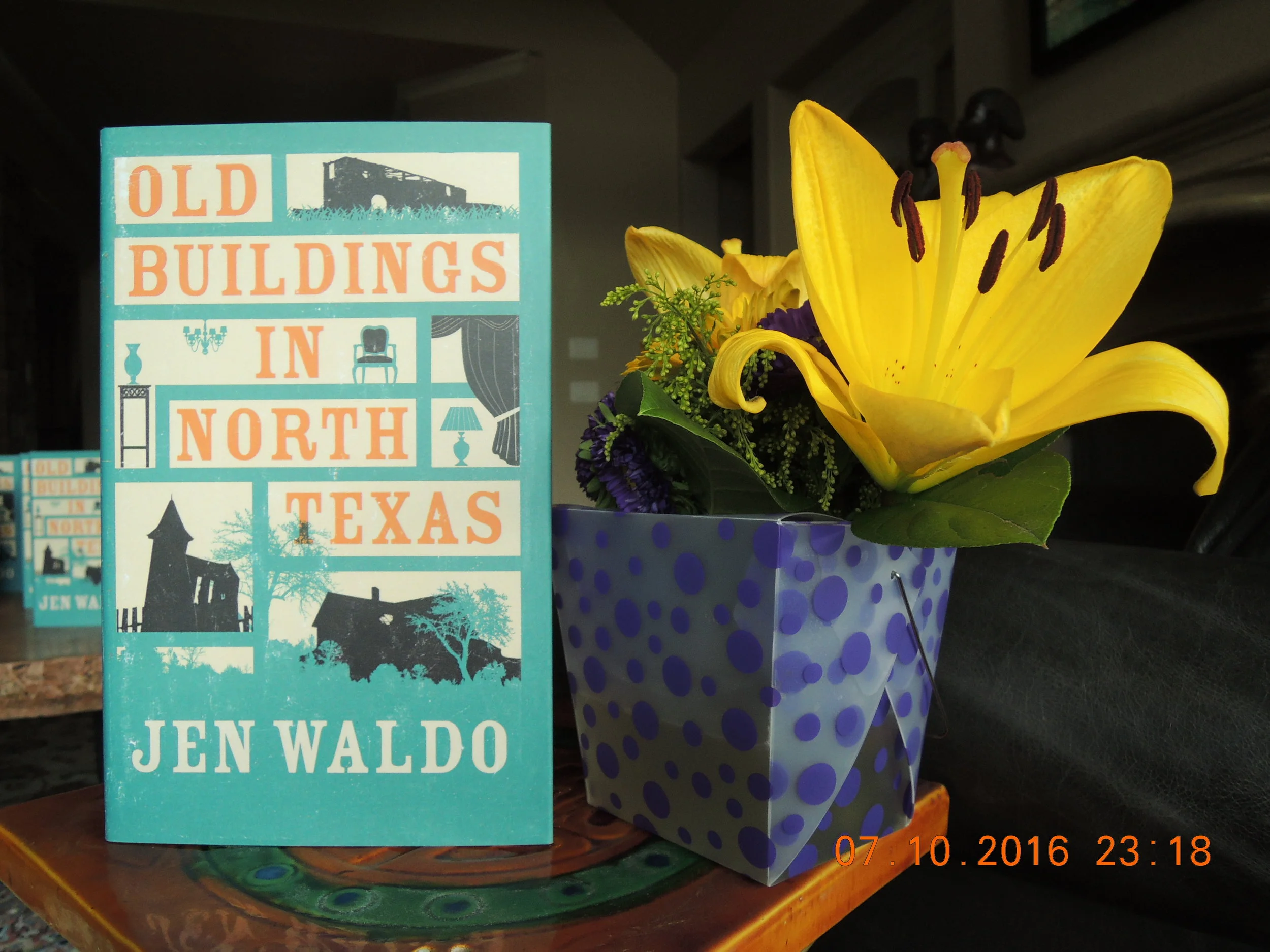

The publishers have done a beautiful job. The color scheme is teal, gold, and cream, quite eye-catching. I have several copies and I’ve rearranged them around the house so that I can see one every time I enter a room. I’m obnoxiously proud. OBiNT’s success is in the hands of the readers now—and I’ll share a thought about that.

The other day an old friend asked me what the novel was about. This is a reasonable question that I’ve come to expect. I gave my friend the nutshell version—a cocaine addict returns to her hometown and, feeling confined, takes up exploring abandoned buildings as a hobby. There’s more to it than this, of course, but during a verbal exchange this is about as much as the average attention span can absorb.

As I related the simpled-down version, I could see her expression turning sour. It wasn’t her thing. She didn’t approve of a story about a cocaine addict. She couldn’t imagine how so depressing a subject could be interesting or entertaining. I wasn’t surprised by her reaction. I’ve known her for years, and she simply doesn’t read. Though it’s impossible for me to fathom, many people don’t.

Despite her reaction, I have faith in the work. I have, after all, been called, “a unique and astonishing new voice in fiction.” My writing style is conversational, making it an easy read; it’s amusing, but not shallow. I love Olivia, the main character, and will admit that she and I share the same dry sense of humor—and I think I’m pretty damned funny. I cackle over my keyboard all the time. My friends who’ve read Old Buildings in North Texas tell me that, as they progress through the narrative, they hear my voice in their heads. Whoa. That can’t be pleasant. Try not to do that.

As to the response to the book, people who know me will be more critical than strangers. I don’t know why, but that’s the way it is. And people who don’t know me will think they do, simply because I’m that convincing. So let me be clear: I am not a cocaine addict. I do not smoke, though I sympathize with those who do. I don’t venture into abandoned buildings. And I don’t endorse secretiveness and stealing. On the other hand, people who are good all the time are boring, while flawed characters are stimulating.

And so, as Old Buildings takes flight, I request positive and supportive feedback. A five-star rating, and especially a comment or review on Amazon would mean a lot to me.

Now I move on to Why Stuff Matters, my next novel, which will be on the shelves in the next six months, give or take.

Sam and Julia gave me flowers to celebrate.

An army. I plan to save them to autograph at readings. I'll send an autographed copy at cost (don't want to go broke!) to anyone not named Waldo who promises to write a review on Amazon.

I made an advertising tableau of the sunglasses Sam gave me. The lenses are polarized and mirrored. I like mirrored lenses because people can't tell that I'm asleep.

Here we are at Saltair, in Houston. Though the red eyes make us look possessed, we're really quite normal. It was a great evening.